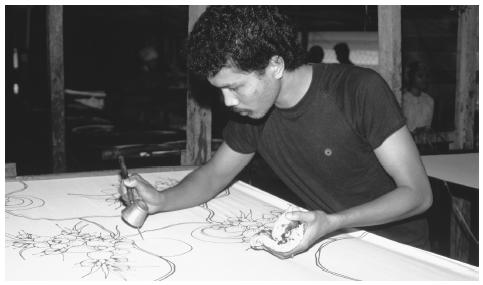

The east coast state of Kelantan is charming destination with colourful traditions, interesting pastimes and superb handicrafts. Watch captivating activities such as top-spinning, giant kite-flying or woodcarving. The batik and songket fabrics produced by cottage industries here are among the best in the country. Its laid-back atmosphere, rustic charms and friendly locals add to Kelantan's appeal.

Accommodation in the capital city, Kota Bharu, ranges from star-rated hotels to affordable rooms. In other main towns, visitors can find comfortable inns, rest houses and modest hotels. The state has a tempting variety of local delicacies. Continent food is available at major hotels while fast food can be found at main towns.

Among the popular places of interest are, Cultural Centre or locally known as Gelanggang Seni. It is a veritable showcase of the state's rich cultural heritage. You can watch an enthralling range of traditional performance such as shadow puppetry (Wayang Kulit), Malay martial arts (Silat), top-spinning (Gasing), giant kite flying (Wau Bulan) and musical performance.

Mount Stong is one of the most popular eco-adventure destinations in Kelantan. Mount Stong rises majestically at a height of 1,433m. Trek to view a diversity of flora and fauna, including Rafflesia, the world's largest flower. A highlight is the spectacular Jelawang Waterfalls, acclaimed to be the highest in Southeast Asia.

Wat Photivihan Buddhist Temple is one of tourist attraction in Kelantan. It houses a 40m long statue of reclining Buddha and believed to be the second longest in the world and the longest in Southeast Asia.

Live with a friendly local family and join their interesting pastimes. Home stays can be experienced at the villages of Renok Baru, Pantai Suri and Blok Ulu Kusial.

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Yazid_Malek

Kelantan, Cradle of Malay Culture

Posted by jeng_llot at Thursday, October 01, 2009 Labels: Culture and traditions, kelantan, kota bharu, malay, silat, wayang kulitTen Essential Things to Do When You Visit Malaysia

Posted by jeng_llot at Monday, September 28, 2009 Labels: Culture and traditions, malaysia, Mount kinabalu, petronas towers, putrajaya, wayang kulitMalaysia is a great place to go to if you are the kind of person who loves both the environment and the city. Amazingly, Malaysia can offer both for you - from its natural treasures, to its man-made architectural wonders. You will find Malaysia to be a country not only rich in resources but also in culture.

1.) Rafflesia, Pitcher Plant and other rare plant species

The list of plant species you can acquaint yourself with in Malaysia is very extensive. In fact, Malaysia is home to almost 8,000 flowering plant species, some of which are exclusively found only in Thailand. You can find the world's largest flower, the Rafflesia, here in Thailand, and you can also find other rare plant species such as the Pitcher Plant.

2.) Malaysia's wildlife reserves and natural parks

But your trip with nature in Malaysia ought not to stop there. There are also wildlife reserves and natural parks in Malaysia, and only in Malaysia can you witness the gathering of so many animals. Orangutans, lizards, insects, bears, elephants, tapirs, rhinoceroses, and so many other endangered animals are well-protected in Malaysia.

3.) Wayang Kulit

Experience the richness of Malaysia's culture by watching the shadow-puppet theater that only professes too much how the Malaysians deal with each other. It also shows how remarkably well preserved their culture has been throughout time. There are also other unique forms of theater art in Malaysia.

4.) Petronas Towers

The Petronas Towers was once the tallest skyscraper in the earth. Today, the glamour of the towers has not vanished at all, and you have the chance of seeing the towers firsthand by visiting Kuala Lumpur. The astounding command the Petronas Towers has over the sky will surely leave you breathless.

5.) Mount Kinabalu in Borneo

You should pay a visit to Mount Kinabula in Borneo. The mountain has the highest peak in the whole Malay Archipelago. It is also a good place to relax and have some quality time with your family in the comfort of nature.

6.) Convention Center in Putrajaya, Malaysia

The function of the convention center in Malaysia is similar to that of the White House. It is actually a place where important government issues and functions are placed. You may not know this, however, because of the architectural beauty of the place but something you will surely revel upon.

7.) Sultan Ahmad Shah Mosque

Religion plays an invariable role in Malaysia. Sultan Ahmad is actually one of the recently built mosques, and yet, it has gained worldwide attention because of the beautiful dimensions of the place, a usual trait in mosques. Sultan Ahmad is one of the examples of classic yet modern Islam architecture.

8.) Longhouses in Sarawak

Longhouses are commonplace in Malaysia, but you might want to take a moment and visit these houses. These are houses built over rivers. You will surely marvel at how ingenious the houses' designs are, inasmuch as it has stood the test of time.

9.) Terengganu State Museum

A visit to Malaysia can never be complete without a visit to one of Malaysia' national museums. Before you think that Terengganu State Museum is just like any other museum, think again. It is actually one of the largest museums in Southeast Asia, and it houses diverse forms of art and archaeological finds exclusive to the place. The architectural structure and design of the place itself will mesmerize you.

10.) Istana Kenangan in Kuala Kangsar

Istana Kenangan is a sort of transient house built exclusively for the sultan whenever he would visit the place. What is so unique about this place (aside from its being historic) is the fact that no nails were used to construct the building. This is truly an architectural wonder.

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Jonathan_Williams

Experience the Many Festivals and Events in Malaysia

Posted by jeng_llot at Friday, September 25, 2009 Labels: Chinese New Year, Culture and traditions, Festivals, malaysia, Mega Sales, Merdeka DayMalaysia is a colorful country not only for its exotic beauty and amazing culture, but also of the many festivals that is celebrated by Malaysians. Every Malaysian celebration is very vibrant and lively. One will definitely enjoy being a part of these amazing events.

Here are some of the well known festivals and celebrations in Malaysia:

• Chinese New Year - like any other New Year celebration, the Malaysians celebrate theirs with such vigor. Fireworks and lots of colorful craze are seen. The whole country is really multicolored and vibrant during this occasion.

• Gadai Dayak - the Malaysian's celebration for the harvest seasons. This is to give appreciation to their gods who blessed the Malaysians with good harvest. During this occasion, locals eat and drink together. There are also dance performances by the members of the community. The Gadai Dayak is celebrated during the end of May until mid July. Malaysians are always in their traditional clothing and the elders perform rituals and services.

• Malaysia Water Festival - held from the second week of April until the month of May. This occasion is managed and organized by the Malaysia's Ministry of Tourism. The celebration is all about water sports activities. There are competitions and games that involve water tricks and races. The celebration is then completed with singing and dancing of the locals with their traditional dances.

• Merdeka day - the Malaysians' own celebration of Independence Day. It is celebrated in August 31st, and is their National Day. During this day, all the streets of Malaysia are packed with music, parades, and people dancing around. People are out blowing horns and trumpets making loud noises around their community.

• Tadau Kaamatan - held during the month of May and lasts for two days. The whole celebration is to commemorate the culture of Sabah's largest ethnic group. The tribes conduct rituals and give honor to their gods. There are also a large variety of foods that are served during the Tadau Kaamatan. Residents enjoy indulging with these tasty and delicious foods for the entire celebration.

• Malaysia Mega sale Festival - probably the most favorite event of all shopaholics. This is to celebrate Malaysia's big gross from its shopping industry and to commemorate this; the Malaysia's tourism department conducted a Mega sale festival. Almost everything that is sold in all shopping stores in the country is on sale during this event. One can enjoy shopping with the lowest prices shops has to offer. The country's shopping department stores are always swarmed with thousands of people buying and treating themselves with bargains and discount prices.

These are just some of the many well known events in Malaysia. Whatever the country celebrates, definitely is a must see for all.

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Pinky_Mcbanon

10 Reasons Why It's Worth Visiting Malaysia

Posted by jeng_llot at Thursday, September 24, 2009 Labels: Cherating, Culture and traditions, Kuala Lumpur, Langkawi, Malacca, malaysia, Pangkor, Pork Dickson, TiomanMalaysia is a beautiful country and a popular tourist destination. Its unique culture, incredible climate, beautiful scenery and delicious cuisine are only a few of the reasons why Malaysia is considered to be one of the best holiday vacation spots in the world.

1. Kuala Lumpur is one of the best reasons to visit Malaysia. It is the capital of Malaysia and is also known as the 'Garden City of Lights'. Its shopping complexes and malls offer a choice of traditional handicrafts as well as branded products from all over the world. The mega sales that are held annually all over the country attract shoppers from all over Southeast Asia.

2. Malaysia offers an amazing range of cuisines to suit all palates and budgets. The different cuisines available include hot and spicy Malaysian dishes, exotic Chinese delicacies, rich Indian cuisine and a multitude of Continental dishes.

3. Sightseeing in Malaysia is a treat in itself. The country has a plethora of exotic destinations that attract tourists from all over the world, including islands, beaches and forests. Some wonderful places worth visiting are Langkawi, Cherating, Port Dickson, Labuan Island, Tioman Island, Pangkor Island and Redang Island.

4. Malaysia is famous for its beautiful heritage sites like the Churches in Malacca and the Malacca Museum, the Mahamariamman Temple in Kuala Lumpur and the Snake Temple in Penang.

5. For those who love exploring the outdoors, it would be worth visiting the Cameron Highlands, Frasers Hill, Berjaya Hills and Genting Highlands.

6. Malaysia's natural beauty is at its most resplendent in the rainforests. The best places to see the splendour of the rainforests would be Kinabalu Park, Kuala Selangor Park, Endau-Rompin and the Mulu national park.

7. A typical tour for lovers of wildlife would include a trip to the Botanical Garden and Bird Park, in addition to the Bukit Jambul Reptile farm.

8. Accommodation in Malaysia spans a wide range of hotels and resorts that appeal to all tastes and budgets. There are high end five star facilities such as the Taj Resort in Langkawi, Berjaya Time Square in Kuala Lumpur, Bayview Beach Resort in Penang and the Berjaya Langkawi Resort, to name a few. Among the hotels that offer good deals are the Holiday Inn Malacca, the Andaman in Langkawi, Citrus Hotel in Kuala Lumpur and the Dorsett Penang.

9. Getting around Malaysia is not difficult. and visitors can travel through the region via air or road. One of the best transport options open to travellers are the car rentals from places like Hertz and Hawk that can take you anywhere in Malaysia. Luxury buses are also available between Malaysia and Singapore.

10. Malaysia still has a fascinating tribal culture. A visit to Sabah provides an opportunity to observe the indigenous tribe in their natural environment.

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Orson_Johnson

Ethnic groups urged to preserve culture and traditions

Posted by jeng_llot at Wednesday, August 12, 2009 Labels: Culture and traditions, ethnic, Miri, SarawakMIRI: More than 30 native ethnic groups in Sarawak have been advised to record down their cultural heritage and unique traditional practices so that they do not end up losing these priceless assets while in their pursuit of development and progress.

These assets are irreplaceable and cannot be compensated by material advancements, said Deputy Chief Minister Tan Sri Dr George Chan Hong Nam.

‘’No amount of material progress can ever replace the unique lifestyles, cultural identities and traditions that we have,” he said when launching the Sarawak 2009 Gong Festival at the Miri Oil Musuem here recently.

Preserve culture: dr chan (right) exchanging souvenirs with Manyin during the launch of the Sarawak Gong Festival 2009.

Preserve culture: dr chan (right) exchanging souvenirs with Manyin during the launch of the Sarawak Gong Festival 2009. ‘’The natives in Sarawak have shown to the world that they are indeed special. Their way of life and traditional practices cannot be found anywhere else.

‘’Don’t lose these treasures. Keep them alive. What is the point of gaining development in the material sense and yet lose the cultural assets that we have inherited from our forefathers,” he added.

Dr Chan said each ethnic group in Sarawak have their own songs, musical instruments, gongs, dances, traditional attires, language and dialects and traditional practices that no other has.

These must be preserved in their entirety, he said, stressing that those organisations in the community responsible for promoting these arts must find ways to record them in audio and visual forms and then ensure the youths learn and continuously practice them.

State Tourism Minister Datuk Michael Manyin said his ministry would organise the gong festival on an annual basis and turn it into another major tourism attraction.

‘’So far, we have successfully promoted the Rainforest World Music Festival in Kuching and the Miri International Jazz Festival and turn them into big tourism events.

‘’I think the gong festival can have similar appeal for tourists.

“In Sarawak, the gongs are used for different reasons and every ethnic groups have different types of gongs that can produce different sounds and beats,” he said.

Malay Survival Hinges On Preservation Of Culture, Tradition

Posted by jeng_llot at Monday, July 20, 2009 Labels: Culture and tradition, malay, Nazrin Shah, Raja Muda PerakThe Raja Muda of Perak, Raja Dr Nazrin Shah has called on the Malays to safeguard their culture and tradition as these are crucial to their survival as a race.

He said that the Malays already had a unique identity, one "which is tied by customs, knotted by language and coated by religion."

He also called on them not to take for granted the Malay privileges as provided for in the Federal Constitution, namely in clauses pertaining to Islam, Rulers' Institution, Malay customs, Malay language and special privileges.

Raja Nazrin said the survival of the Malays as a race hinged on the very factors which had given them identity, namely religion, language, culture and traditions, and the Rulers' Institution.

It would be unfortunate, therefore, when attempts were made to undermine the traditions and institution, he said.

"It would be to the great detriment of the survival of the Malay race if traditions and institutions are no longer respected and seen instead as antithesis to rational thinking, modernity and science.

"How unfortunate would it be for a generation to view traditions as 'an ignorant practice, inconsequential and dogmatic'," he said at the launching of a book, The Malays, at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) here.

The book is written by Prof Anthony Milner, an Asian history professor at the Australian National University.

Also present were the Raja Puan Besar of Perak Tuanku Zara Salim, UKM Vice-Chancellor Prof Datuk Dr Sharifah Habsah Syed Hasan Shahabuddin and Bernama Chairman Datuk Seri Annuar Zaini.

Raja Nazrin said that in wading the tide of globalisation and in facing political dynamics currently taking place in the country, the Malays could be caught in crossroads and faced with two possibilities.

The first, he said, was that they would continue to survive and thrive, and emerge as a supreme race in a globalised world.

"The second possibility, God forbids, is that they would be swept away by the tide of globalisation and become weak, devoid of any cultural root.

"In the end, the Malays would remain only as a name in folktales," he said.

It was therefore important that the Malays avoid committing the folly of Pak Kadok, a character in the old Malay fable who lost his village because of his foolishness.

He also cautioned the Malays to be wary of what he said as "radical attempts" to undermine their strength.

Raja Nazrin also expressed appreciation to Prof Milner's recognition of the Rulers' Institution as an important heritage of the Malay race.

He said that the interest shown by non-Malays in carrying out studies on the Malays showed that the race continued to attract interest among intellectuals abroad.

He called on the Malays to appreciate Prof Milner's efforts.

The least they could do, he said, was to make the book a compulsory reference for students taking Malay studies.

Sabah Culture and Heritage

Posted by jeng_llot at Thursday, July 16, 2009 Labels: culture, ethnic, heritage, kota kinabalu, sabahState Mosque

In Kota Kinabalu, this gold-domed state mosque is centrally positioned and overlooks most of the town. It reflects contemporary Islamic architecture and can accommodate 5,000 worshippers. There is a special balcony with room for 500 women to pray. For a panoramic view of the city and its waterfront, go up to Signal Hill nearby.

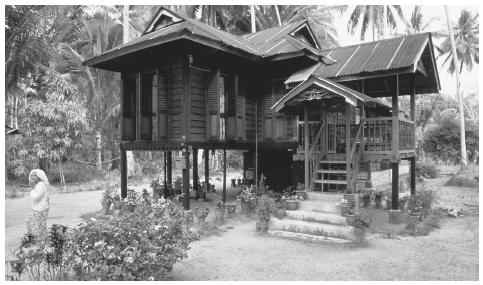

Sabah State Museum

Located on Bukit Istana Lama, a hill behind the State Mosque, this museum was built in the longhouse style of the Rungus and Murut tribes. The museum has a wealth of historical and tribal treasures, and handicrafts made by the indigenous peoples. The major highlights are the exhibits of life-size traditional houses belonging to six ethnic groups.

There is a good section on Sabah's fascinating flora and fauna, an art gallery and a Science Centre. The latter has a large exhibition on the oil and petroleum industry. Within the complex are a restaurant, coffee-house and an ethno-botanical garden with an artificial lake and a souvenir shop.

Fronting the Sabah State Musuem is an Ethnobotanic Garden that is open daily from 6:00 am to 6:00 pm, whose huge range of tropical plants is best experienced on one of the free guided tours that is operated daily at 9:00 am & 2:00 pm except for Fridays. Bordering the garden are full-sized models of houses from Sabah's ethnic groups.

Sabah Foundation Building

The 31-storey Sabah Foundation Building at Likas Bay, 10 minutes from Kota Kinabalu, is a magnificent, futuristic glass-shrouded tower with 72 sides! It is a striking landmark which can be seen for miles around.

The 31-storey Sabah Foundation Building at Likas Bay, 10 minutes from Kota Kinabalu, is a magnificent, futuristic glass-shrouded tower with 72 sides! It is a striking landmark which can be seen for miles around.

Atkinson Clock tower

Located at the city centre of Kota Kinabalu, the Atkinson Clock Tower was built in memory of the first District officer of Jesselton, Francis George Atkinson. He died of 'Borneo fever' in 1902 at the age of 28.The clock was originally lit up at night and acted as a beacon for shipping vessels. It was one of three buildings that survived the destruction during the Second World War. Over the years it has undergone renovations and repairs but has managed to retain most of its original characteristics.

Signal Hill Observatory

For a view of Kota Kinabalu city and harbour, head for the observation point on Signal Hill (Bukit Bendera). If you decide to walk (which will take approximately

15 - 20 minutes from downtown) rather than taking a taxi, there's a shortcut up the hill beside the old Clock Tower, just beyond the Police Station.

Water Villages

Visit a settlement of the local "Bajau", descendants of pirates who set foot on the land in the early 19th Century. Presently, these people are fishermen who reside in a village built on water. The spectacular sights are the houses which stand on stilts in the water and are connected by narrow wooden planks.

Kampong Monsopiad (Monsopiad Cultural Village)

The Monsopiad Cultural Village was founded in memory of the great Kadazan Warrior and head-hunter Monsopiad. The traditional village is a historical site and the only cultural village in Sabah. It was built on the very land where Monsopiad lived and roamed some three centuries ago. The Village is run by the direct descendants of Monsopiad. More than being a museum, the Monsopiad Cultural Village aims at documenting, reviving and keeping alive the culture and traditions of the Kadazan people. You can also watch cultural dances and try using a blowpipe. Kampong Monsopiad is approximately 10km south of Kota Kinabalu.

St. Michael's Catholic Church

Located in Kampung Dabak 10 km south of Kota Kinabalu, this church was built in 1879, and is Sabah's oldest church.

Central Market

There is a water village along the seafront known as Kampung Ayer where the jetties are lined with fishing and commercial craft.

The bustling Central Market sits mid-way along the waterfront. The fish market here teems with many varieties of fresh seafood. An early morning excursion will allow visitors to watch the fishermen unloading their catch directly onto market tables. All around them Kadazan women display fresh fruit and vegetables brought down from the farms in the foothills of Mount Kinabalu.

The Orang Asal of Malaysia

Posted by jeng_llot at Monday, July 13, 2009 Labels: culture, kampung, malay, malaysia, orang asli, traditionsFlittering like a hummingbird amid a patch of flowers, a little mobile stall shifts locations in Kuala Lumpur packed with the cultural works of sixteen different Orang Asal ethnic groups. Despite the urban setting, these handicrafts have roots throughout the rural landscape of Malaysia and are usually purchased directly from the artisan.

Welcome to the Gerai OA

'Orang Asal/Asli' is a Malay term for Original People. Orang Asal represents the indigenous peoples of Peninsular and East Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), while Orang Asli refers specifically to the indigenous minorities of Peninsular Malaysia whom are distinct from the mainstream population in Peninsular Malaysia.

"They have their own religion, language, customs and worldviews which they are determined to transmit to future generations. More importantly, the Orang Asal have a special relationship to their traditional land," explains Dr.Colin Nicholas, co-founder and coordinator of the Center for Orang Asli Concerns (COAC).

There are currently, according to the Jabatan Hal Ehwal Orang Asli (JHEOA) 149,512 Orang Asli, whereas the Orang Asal number to 2.1 million.

Rare and Unique Orang Asal Craft

The founder of the Gerai OA, Reita Rahim, goes from kampung (villages) to kampung across Malaysia, sourcing rare and unique craft from gifted Orang Asal craftsmen and women. The Gerai OA is non-profit and is run by a group of volunteers with the purpose of sharing with others the arts of the Orang Asal and at the same time encouraging the survival of the tradition of craft making.

An example of craft for sale would be the traditional Orang Asli puzzles. One particular puzzle, known as the Jah Re Noi, usually gets many hands tugging wildly at. This Semai (Orang Asli subgroup) puzzle is a piece of entwined rattan with a thin looped rope stuck in the middle of it.

The objective of the puzzle is to remove the rope from it. Legend has it that if someone is lost in the jungle due to mischievous spirits confusing them, all that person needs to do is make and leave behind one Jah Re Noi puzzle and the spirit will get so engrossed in solving the puzzle that it will leave its victim alone.

Cultural survival

One of the main threats faced by the Orang Asli is the "non-recognition of their rights to traditional land" as their land has been being progressively taken for development, according to Dr. Nicholas. This is because they are not "recognized as indigenous people of this land." "The Orang Asli are not anti-development or not against the virtues of modernization. In fact, Orang Asli cultures/identities have the potential to be viable but they are vulnerable to the many challenges that threaten their culture and their identity as a unique people."

The Mah Meri subgroup of the Orang Asli is one of the many groups who has lost much of their rights to their traditional land at Pulau Carey, and are struggling to maintain their unique culture and identity as represented by their wooden cravings that were awarded 6 UNESCO seals of excellence last year. Deforestation to make way for oil-palm plantations in Pulau Carey has led to the loss of Pulai (Alstonia sp.), a tree which was used to make the wooden masks that is traditionally believed to represent their moyang (ancestors). Now that it is extinct on the island, they have resorted to use Pokok Nyireh Batu (Xylocarpus sp.), a mangrove forest tree which use to be used only for the cravings rather than the masks. This mangrove tree is however becoming increasingly harder to find. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is currently sponsoring replanting schemes for these plants.

While the woodcarving is done solely by the Mah Meri men, the women have recently displayed their own skills with weaving. Intricately weaved curl work pouches known as bujam lipo' are made from pandanus strips and are one of the hot items at the Gerai OA. Traditionally used as a 'hold all' for small items such as money, areca nuts or tobacco, the contemporary uses of these pouches are as hand phone holders or as purses.

Some of the other popular items are also the accessories by the Rungus people of Sabah. Their reputation for using beads and turning them into beautiful and unique accessories can be seen littered in a mosaic of colors across the table at the Gerai OA.

"The new designs are to better suit the Kuala Lumpur market. If you go to Sabah, you may not find what you can find here at the Gerai OA," Reita explains.

The very source of the new beaded designs is actually from a group of Rungus women from Kampung Tinanggol in Sabah. This group of 20 Rungus women consists of selected elderly and single mothers who work together to help better their economic standing.

"The profit from the sales are used to pay for their children's schooling fees or used as investment, such as to open ladang (fields)," explained Reita.

The group, headed by Malina Soning, works together to come up with new designs and color combinations to compliment the current trends. Handmade bracelets, necklaces, rings, key chains and even hairclips, using traditional technique, now come in many attractive colors and patterns.

Malina explained that the need for these new innovations is to compete for the tough market where mass produced items can be bought at much lower prices. Others have also begun to make imitations of their traditional craft. At the moment their focus is on the beads as they are easy to acquire and transport, and the demand is there.

"The Gerai OA is not just about selling, but about educating people about Orang Asal and Orang Asli," explains Reita. This is why the gerai (stall) also carries books, video documentaries and music CDs about Orang Asal/Asli. People are also encouraged to stop by and test out the many traditional musical instruments laid out for sale and display. Support for the Gerai OA would go a long way to help improve the economic standing of various Orang Asal groups and encourage the survival of their traditional arts.

Written by Puah Sze Ning(http://www.wildasia.org/main.cfm/support/Crafting_Culture)

Malaysia Culture & Heritage - Traditional Games & Pastimes

Posted by jeng_llot at Friday, July 10, 2009 Labels: congkak, culture, gasing, malay, malaysia, silat, traditions, wau, wayang kulitExperience the Expressions of Community

Malaysians strong sense of community is reflected in many of their traditional games and pastimes. These activities are usually held during festivities such as before or after the rice harvest season and to usher in the new spring.

Silat

This fascinating Malay martial art is also an international sport and traditional dance form. Existing in the Malay Archipelago for centuries, it has mesmerising fluid movements that are used to confuse opponents. It is believed that practising silat will increase one's spiritual strength in accordance with Islamic tenets. Accompanied by drums and gongs, this ancient art is popularly performed at Malay weddings and cultural festivals.

Sepak Takraw

Sepak takraw, also known as sepak raga, is a traditional ball game in which a ball made by weaving strips of buluh bamboo or rattan together is passed about using any part of the body except the lower arms and hands. There are two main types of sepak takraw: bulatan and jaring. Sepak raga bulatan is the original form in which players form a circle and try to keep the ball in the air as long as possible. Sepak takraw jaring is the modern version in which the ball is passed across a court over a high net.

Wau

A wau is a traditional kite that is especially popular in the state of Kelantan on the East Coast of Malaysia. Traditionally flown after the rice harvest season, these giant kites are often as big as a man - measuring about 3.5 metres from head to tail. It is called wau because its shape is similar to the Arabic letter that is pronounced as 'wow'. With vibrant colours and patterns based on local floral and fauna, these kites are truly splendid sights.

Gasing

A gasing is a giant spinning top that weigh approximately 5kg or 10lbs and may be as large as a dinner plate. Traditionally played before the rice harvest season, this game requires strength, co-ordination and skill. The top is set spinning by unfurling a rope that has been wound around it. Then it is scooped off the ground, whilst still spinning, using a wooden bat with a centre slit and transferred onto a low post with a metal receptacle. If expertly hurled, it can spin for up to 2 hours.

Wayang kulit

Wayang kulit is a traditional theatre form that brings together the playfulness of a puppet show, and the elusive quality and charming simplicity of a shadow play. The flat two-dimensional puppets are intricately carved, then painted, by hand out of cow or buffalo hide. Each puppet, a stylised exaggeration of the human shape, is given a distinctive appearance and not unlike its string puppet cousins, has jointed "arms". Conducted by a singular master storyteller called Tok Dalang, wayang kulit usually dramatises ancient Indian epics.

Congkak

Congkak is a game of wit played by womenfolk in ancient times that required no more than holes in the earth and tamarind seeds. Today, it has been refined to a board game. It consists of a wooden board with two rows of five, seven, or nine holes and two large holes at both ends called "home". Congkak, played with shells, pebbles or tamarind seeds, requires two players

Chingay

Famously from the state of Penang, Chingay or The Giant Flags Procession is a spectacular procession that celebrates the arrival of spring during the New Year season. Its trademark elements are giant triangular flags and lanterns. These flags equally huge poles are balanced on performers foreheads, chins, lower jaws and shoulders. Other entertainers include dancers, jugglers and magicians.

Sepak manggis

Sepak manggis is a unique outdoor game played by the Bajau and Iranun men of Sabah. Forming a circle and facing each other, players aim to strike the bunga manggis floral carrier that dangles from a 10-metre high pole. The winner will be rewarded with money, gift or edibles, which are in the carrier.

|

Temple Cave has a ceiling looming over 100 meters overhead and features ornate Hindu shrines. To reach it, one has to climb 272 steps, a feat performed by many Hindu worshippers on the way to the caves to offer prayers to their revered deities. During the annual Thaipusam (Hindu festival in honor of Lord Murugan) between January and February, as many as 800,000 devotees and other visitors throng the caves and make this climb. Chanting devotees carry a statue of the deity, Lord Murugan, up the 272 steps that lead to the shrine. As a form of penance or sacrifice, entranced worshippers carry a Kavadi, which is a large, elaborately decorated wooden frame. The Kavadi is attached to their flesh (e.g. skin, cheeks & tongue) with a variety of sharp skewers and metal hooks, to no apparent discomfort or pain! Accompanied by the incessant beat of Indian drums and shouts of encouragement, the procession is testimony to the power of religious conviction. A little below the Temple Cave is the Dark Cave. It is a 2km long network of relatively untouched caverns containing a large number of cave mammals & a living fossil (trap door spider). However, access to this cave is restricted. Permission must be obtained from the Malaysian Nature Society and guidelines must be strictly followed. At the foot of the steps is the Art Gallery, in which statues and wall paintings depicting Hindu mythology are displayed. Access to this cave is via a concrete walkway spanning a small lake |

African Culture & Tradition

Posted by jeng_llot at Tuesday, June 23, 2009 Labels: african, culture, traditions, weddingMany African Americans desire a wedding which reflects their native heritage. You must understand where ancestors may have originated from to plan the wedding reflecting your heritage. We have included many regions from Africa, and certain traditions in the United States. Please feel free to contact us with your comments, and any other traditions which you would like us to include. Enjoy!

Major Religious Beliefs

Africa is comprised of many religious and non-religious groups. The major religious cultures are Muslim, Christians (Roman Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Anglican and others), ethnic religionist, non-christian, Hindu and Baha'i.

Wedding Traditions

Here are some African wedding traditions. You may wish to be creative in adapting these traditions to your wedding.

Africa is made up of various different countries, each of which may have their own traditions. Many of these traditions would not be acceptable to the African American bride as it may require lifestyle changes which would be unacceptable.

Pygmie engagements were not long and usually formalized by an exchange of visits between the families concerned. The groom to be would bring a gift of game or maybe a few arrows to his new in-laws, take his bride home to live in his band and with his new parents. His only obligation is to find among his relatives a girl willing to marry a brother or male cousin of his wife. If he feels he can feed more than one wife, he may have additional wives.

Along the Nile, if a man wishes to see his sons well married, he must have numerous sheep, goats and donkeys. When marriage negotiations are underway, the father of the bride will insist that each of her close relatives be given livestock. The grooms problem is to meet the demands while holding enough cattle to support his bride.

Similar to our custom of sending wedding invitations and expecting gifts in return, he makes the rounds of relatives getting contributions for his bridal herd. Each day for a series of wedding days there is a special event. On the first day, or the wedding day, the groom arrives at the bride's homestead wearing a handsome leopard skin draped over his cowhide cape. Usually that will be all.

Nilotes are devoted nudists. Clay, ash, feathers, sandals and a necklace are considered ample dress for any occasion. The bride wears the beaded apron and half skirt of the unmarried girl.

After the private cattle negotiations are publicly and elaborately re-enacted, the bride is taken to the groom's homestead and installed in the compound of her eldest co-wife until a separate place can be prepared for her.

Marriage is a key moment that follows immediately after initiation among many peoples because both events serve to break the bonds of the individual with childhood and the unmarried state, and to reintegrate the individual into the adult community.

Among the Woyo people,a young woman is given a set of carved pot lids by her mother when she marries and moves to her husband's home. Each of the lids is carved with images that illustrate proverbs about relations between husband and wife.

If a husband abuses his wife in some way or if the wife is unhappy, she serves the husband's supper in a bowl that is covered with a lid decorated with the appropriate proverb. She can make her complaints public by using such a lid when her husband brings his friends home for dinner.

To demonstrate the differences of African culture, here are some examples of several Zambian weddings. Although these weddings take place in the same country, difference provinces have different ways of approaching the marriage ceremony. The common thread is the closeness of the bridal family to achieve the goal of a wedding and lasting relationship. Marriage payments are to the family of the bride rather than to the brides parents.

In traditional Zambian society, a man marries a women, a woman never marries a man. It is taboo if a woman seeks out a man for marriage.

In Namwanga, a young man is allowed to find a girl. He proposes and gives her an engagement token called Insalamu. This is either beads or money to show his commitment. It also shows that the girl has agreed to be married. His parents then approve or disapprove his choice. Should they reject his choice, he starts to look again. If they agree, then the marriage procedure begins.

A man who has reached the age for marrying in the Ngoni society looks for a girl of marriageable age. Once he has selected someone, the two agree to marry and tell their respective relatives.

The Lamba or Lima mother started the process of finding a girl for her son to marry. She would search for an initiated girl known locally as ichisungu or moye. (An uninitiated girl was not for marriage until she reached puberty or initiation age.) The mother of the man visited neighboring villages looking for the right unmarried initiated girl. When she found one - one whom was from a good family according to her judgments, not the son's, she would go to the mother of the girl and tell her that she wanted her son to marry her daughter. The mother would then discuss this with her daughter, the man's mother would return home and come back a few days later for an answer.

Many Bemba men began their marriages by first engaging young girls below the age of puberty. The young girl is not consulted with at all. The girl would go to her future husband's house, sometimes alone, most often with friends after the marriage price was negotiated. On her first trip to his house she did not talk to him or enter his house without small presents being given to him. She would then speak to him and do a lot of housework for him. She would do what she thought was good for her future husband. This period of courtship was known as ukwisha. During this period, she was responsible for the man's daily food. The groom had to build his own house in the village where he was living, or in the village of his parents-in-law.

The go-between to initiate the marriage negotiations is the commonalty of all marriage arrangements in Zambia.

In Namwanga, the man's parents arrange for a Katawa Mpango. This is a highly respected person representing the groom's interests. The groom's family gets ready and decides on a day to visit the girl's family. The girl, after receiving the Insalamu, takes it to her grandmother. This is the official way her family is informed.

Her grandmother informs her parents and the family. They either accept or reject the proposal. Whatever the decision, they then wait for the man's family to approach them by way of the Katawa Mpango. When he visits, he traditionally will take a manufactured hoe, wrapped in cloth with a handle. The hoe is a symbol for the earth, for cultivation, for fertilization. He carries white beads and small amount of money. The beads and money are put in a small plate covered with another small plate of equal size.

The go-between must know the house of the girl's mother. Traditionally, he knocks on the door and is invited in. Dramatically he falls on his back and claps his hands. This is to indicate to the girls marriage panel that he is on a marriage mission. Then he places the hoe and plates on the floor halfway between the marriage panel and himself. He then explains his mission and is asked many questions by the girl's family. If no decision is made by the girl's family, the hoe is taken back, beads and money are taken by the girl's family. If a decision of rejection is reached that day, the hoe is taken back. If they accept, the plates are opened and the hoe is accepted once the girl acknowledges she knows the source.

The go-between reports to the man's family. If the answer is positive, the family starts to prepare marriage payments and a marriage council is instituted to look into affairs. The go-between returns on a specified day for details on the marriage payments. When he returns, exotic foods are prepared for his second journey by the man's family.

In pre-colonial period, the marriage payment included cattle (four or more), chickens and a cow (if the girl was a virgin). This payment went to the mother in appreciation for giving birth to the girl. Other payments are demanded nowadays -- a chitenge cloth, canvas shoes and a dress -- 2 blankets, a pair of shoes and a suit for the father.

A traditional wedding of a bride from Morocco is expensive and impressive. The dowry is paid before a notary and is spent on the bride's trousseau and new furniture. The jewelry she receives must be made of gold (rings, bracelets, necklaces and earrings). During the engagement period, (which usually lasts six months to two years) the prospective groom sends his bride-to-be gifts of cloth, gowns and perfume on feast days.

Five days before the wedding, a mattress, blankets, and other necessities are carried into the bridal chamber. The bride is given a bath in the hammam. Her female wedding attendants, called negassa, closely supervise. She is applied make up (including henna-stained designs) to her hands and feet. She is then dressed in her embroidered wedding finery of white robes. She is then placed behind a curtain, symbolizing her transition to a new life.

The next evening the bride, while sitting on a round table, is carried on the shoulders of her wedding attendants as they are singing and shouting walking to the bridal chamber. This ritual of carrying her to the bridal chamber while festivities go on happens for the next seven days. The wedding attendants stand behind a screen to verify the bride's virginity and witness her defloration. After a second ritual bath, the wedding attendants leave the house and the couple are left alone.

Wedding Attire

An African woven cloth serves the function of reflecting personal, societal, religious and political culture. Kente cloth is the primary woven fabric produced by the people of the old Ashanti Kingdom of Ghana. The traditional red, gold and green repeated in the design are liberation colors recognized by children of African descent all over the world.; (red for the blood shed by millions in captivity), gold for the mineral wealth (prosperity), and green for the vegetation of the land of Africa (home).

Boxes arranged in an "X" mean all ideas coming together at one point symbolizing leadership, consensus and the voice of the people. The stepped border motif symbolizes defense against the countless assaults and obstacles encountered in the course of an African lifetime.

Traditional native attire for the female would be a headpiece (a gele'), a loose fitting or grand bou-bou or the wrap skirt (iro), shawl (iborum), and a short loose blouse (buba) made out of the same fabric. The groom wears a pair of slacks (sokoto), shirt (bubba), a long flowing pullover type jacket (agbada) and a rounded box-like hat (fila).

African American couples who chose a more American flare may chose the traditional white bridal gown for the bride and the groom a tuxedo. The traditional color of African royalty is purple, accented with gold. These may be used as accent colors worn by the bridal party.

Malaysian Culture and Traditions

Posted by jeng_llot at Friday, June 05, 2009 Labels: culture, malay, malaysia, malaysian, traditionsAs Malaysia is made up of various races and ethnic groups, you will find that the country exudes a unique and one of its kind traditions and cultures. This is where you will be able to observe a travel experience which is different from any other country you will visit because there is a harmonious and united stand among the people of the country. As such, there are various different types of traditions that are observed by the people of Malaysia throughout the year thereby giving you a different experience every time. Throughout the year, there are celebrations and festivals that are celebrated by Malaysians like the Hari Raya Aidilfitri celebrated by the Muslims and Malays, the Chinese New Year and Mooncake Festival observed by the Chinese, Thaipusam and Deepavali commemorated by the Indians, Gawai festival celebrated by the people of Sarawak and many more all of which are commemorated together either nationally or regionally. Each of these festival comes with its very own reasons and history and this is where we provide you with background information about what they are, how they come about and why are they celebrated.

Malaysia a symbol of ethnic harmony

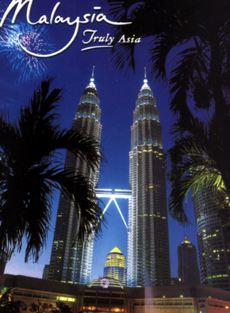

Posted by jeng_llot at Thursday, May 14, 2009 Labels: ethnic, malay, malaysiaKUALA LUMPUR: Twin Towers rising like sentinels in the heart of Kuala Lumpur - that was the first picture of Malaysia to come into our minds when we were invited to this country.

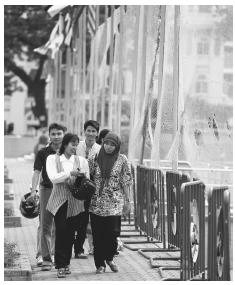

A group of Malaysian women dressed in ethnic costumes welcome visitors in front of a building built in traditonal Malaysian style. [file photo] |

But what really excited us was that our hotel - the Mandarin Oriental - was right next door to the buildings. From the windows of our rooms, the glass-and-steel structures shone under a clear blue sky.

We couldn't resist rushing into the 88-storey towers, which soar 452 metres above street level, even before we had unpacked our luggage.

Costing a whopping US$1.2 billion, they were completed in 1997 and were the tallest in the world until 2003, when a higher building was completed in Taiwan.

"The towers helped Malaysian people build up their confidence," said Tan Sri Dr Noordin Sopiee, chairman and CEO of the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia. "What foreigners can do, we can do."

Towers of confidence

It was at the foot of the towers, that we, in our first ever visit to Malaysia, started our journey of understanding into this country.

The Petronas Twin Tower dominate the skyline of Kuala Lumpur. [China Daily] |

According to Sopiee, lack of confidence was a serious problem for Malaysia in the initial stages of its independence.

At the time, the multi-ethnic state was politically unstable, saddled with chronic and wide income, economic and development gaps, with few unifying features. It had been devastated by a civil war and race riots, had a feeble economic growth rate of only 3.5 per cent, an uneducated population, and no experience in democracy or self-rule.

"We once relied heavily on things like the Twin Towers - something the tallest, or the biggest, or fastest in the world - to help us develop self-confidence," Sopiee recalled. "We were once psychologically and culturally crippled."

Today, however, after 47 years of struggle, although Malaysia still faces some challenges, dramatic changes have taken place in the political, economic and social landscape.

Malaysia has evolved from a rubber and tin economy to become one of the world's most industrialized states, with a 7 per cent economic growth rate, 90 per cent of its exports manufactured goods, and no racial riots since 1968.

Moreover, the country is especially proud of its fast recovery from the Asian financial crisis - its GDP grew 7.4 per cent in the first quarter of this year and is expected to hit 6 to 6.5 per cent for the whole year. The banking sector, devastated by the crisis, has also been consolidated. In the disposal of bad bank loans, a recovery rate of as high as 57 per cent was achieved, compared with some 20 per cent in China.

And its efforts to build a harmonious home for 27 ethnic groups, mainly Malay, Chinese and Indian, have paid off. Malay people account for 58 per cent of the country's total population, Chinese around 25 per cent and Indian 7 per cent, with other small groups making up the remaining 10 per cent.

In this nation of different religions - Islamism, Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, Christianity, Sikhism and Jainism - all the festivals of the different ethnic groups are respected. Several languages, mainly Malay, English and Chinese, are spoken.

"We feel pretty secure here now," said Siew Nyoke Chow, director and group editor-in-chief of the Chinese language Sin Chew Daily. "Malaysia has done a good job in this respect (unifying different ethnic groups)."

An often cited example of the harmonious relationship between different ethnic groups is the fact that many Malay people send their children to Chinese schools.

Nara Jantan, ISIS's senior public affairs and conference organizer, is one of them. She sent her daughter and son to Chinese primary schools.

"They are bilingual at home - we speak English and Malay. They can learn the third language - Chinese - in primary school. That's good for them," said the happy mother.

Actually, it is now very common for Malaysian people to speak several languages. We were surprised to find that most of the people we encountered during our 10-day stay spoke fluent English, even including ordinary taxi drivers and sales people in shopping centres.

To promote English education, the Malaysian Government even requires that mathematics and science courses to be taught in English in primary schools.

"Although Malay is the official language, most people speak English in offices," said Philip Mathews, ISIS Malaysia's co-director of the centre for international dialogue.

The centre's other co-director, Dr Stephen Leong, is even good at telling jokes both in Chinese and English.

But what surprised us even more is the fact that many Malaysian people can speak not only Mandarin Chinese, but also Cantonese and other Chinese local dialects.

Dato' Dr Ng Yen Yen, deputy finance minister, is one of them. When she tried to communicate with us in Cantonese, we could only reply, "Sorry, we can only speak Mandarin."

She said different cultures, different religions and different languages make Malaysia a typical Asian country, and that's what "Malaysia - Truly Asia" - the tourism advertisement often seen on CNN - means. Malaysia has spent millions of ringgit to promote this concept.

The deputy finance minister herself is an earnest advocator of the idea.

She wore a special dress when she met us, with the collar and buttons in Chinese qipao style, a Malaysian batik skirt, and a yellow Indian style shawl.

"With this dress, I can attend any gathering of Malay or Chinese people, and with the shawl, I can enter into any Indian temple," She said, adding that she had designed the golden dress herself.

The elegant government minister with her three-in-one dress and bright smile deeply impressed our group of 15 international journalists and researchers.

But she was not the only charming women we met during our stay in Malaysia.

Women's advancement

ISIS organized about a dozen interviews for us with senior officials, several of whom were women. In addition to Dato' Dr Ng Yen Yen, we also met Datuk Latifah Merican Cheong, assistant governor of the Central Bank of Malaysia, Dato' Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil, minister of women and family development. A female executive spoke to us about the operations of Petronas, Malaysia's national petroleum corporation, and a lady briefed us on the development of the nation's Multimedia Super Corridor.

Cheong, who supervises the central bank's foreign exchange control department, was the first high-ranking woman official we met.

Her eloquent oral presentation on Malaysia's economy and banking sector and to-the-point style when answering questions made us reassess our view and take note of the role of women in Malaysia's social and political arena.

We were later told that three ministries in this country are headed by women - the ministries of women and family development, international trade and industry, and youth and sports. And there are quite a few women deputy ministers as well.

Women architects and engineers are also active, many have participated in the design of Kuala Lumpur's famous skyscrapers. In universities, female students account for over 60 per cent of the total enrolment.

However, Dato' Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil, the minister of women and family development, believes that much still remains to be done to uplift women's status.

She admitted that there is still a need to educate men to fully accept gender equality, and said the concept must be taught in the home, and that women must show that they are "strong."

Her ministry has been holding seminars and training sessions to help women become economically independent.

But another problem now is that many well-educated, successful career women choose to stay home after they get married and have children, she said, adding that her ministry is working to promote job opportunities to allow women to work from their homes.

With her well-cared-for face and stylish dress, this woman minister had a hard time convincing us that she was 51.

"I will be a grandmother soon," said the mother of three children, smiling.

But when asked for her opinion on the possibility of Malaysia having a woman prime minister, she became serious.

"It won't be too long before that happens," she said.

Women organizations are also active in Malaysia. Sisters in Islam is one of them. It is a group of Muslim women studying and researching the status of women in Islam.

Unlike many Chinese women organizations which extend helping hands directly to women suffering from domestic violence and other unfair treatment, Sisters in Islam is mainly engaged in training and studying.

They have also gone to the courts to question discriminatory laws and they often write letters to the editors of newspapers to comment on cases of gender discrimination.

"It has been a long journey to where we are now," said Dato Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil. "But we have made great strides and no one can prevent us from reaching our goals."

That's true even for the whole of Malaysia, a country which has already bade farewell to poverty, racial riots, and political instability and moved onto a fast development track after decades of hard work.

Challenges

But it still faces new challenges - such as how to ensure the quality and speed of such development in the future.

Back in the 1990s, the Malaysian Government began to seriously consider how the approaching Information Age would affect Malaysia and how the country, currently manufacturing and export-oriented, must move to develop a knowledge-based economy.

Their answer was the initiation of the country's Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) in 1996.

"We aimed to cultivate a knowledge-rich society in Malaysia and take the country into the Information Age," said Sharifah Hendon Syed Hassan, with the Multimedia Development Corp, the developer of MSC.

The MSC is the nation's answer to the question of how to jumpstart the development of technology in the country. Physically, it is a 15-kilometre by 50-kilometre area reaching from Kuala Lumpur City Centre (KLCC) to the Kuala Lumpur International Airport.

The MSC is devoted to creating the best possible environment for multimedia companies wanting to create, distribute and employ multimedia products and services.

Several key areas such as e-government, multi-purpose cards and borderless marketing have been identified to spearhead the development of MSC, the official said.

Another ambitious plan is to build Putrajaya, the new administrative centre for the Federal Government of Malaysia which is about 40 minutes drive from KLCC.

Like all the big cities worldwide, Kuala Lumpur is a crowded city, with narrow streets full of private cars - mostly Protons made in Malaysia, shopping centres jam-packed with visitors from all over the world, and row upon row of skyscrapers.

To ease pressures in the overcrowded city and leave more downtown space for commercial activities, the Malaysian Government decided in the mid 1990s to build Putrajaya.

Named after Malaysia's first Prime Minister, Putrajaya has been dubbed Malaysia's first Intelligent Garden City. It is both the new nerve centre of the nation and an ideal place to live, work, conduct business and engage in sports and recreational activities.

This landmark complex stretches over 453 hectares. More than 70 per cent of Putrajaya is devoted to greenery and water with 13 different gardens.

Putrajaya Holdings, a company established to take charge of development of the new area, started construction of Putrajaya in 1996 and completed Phase 1 in 2000 with the delivery of infrastructure and key government buildings including the blue-domed Prime Minister's office and the red Putra Mosque - one of the largest in the nation. It is now in phase 2 of its development, which is expected to be completed in 2005.

Walking along the wide, flower-dotted roads in Putrajaya, appreciating all the brand-new buildings in different styles, or watching birds flying over the man-made lakes, we could not help admiring Malaysian people for building such a miracle in only five years.

If we agree that the Petronas Twin Towers were the source of confidence for Malaysian people in the 1990s, the MSC and Putrajaya will no doubt become the pride of the nation in the 21st century.

Indigenous People Of Malaysia

Posted by jeng_llot at Thursday, May 14, 2009 Labels: malay, malaysia, malaysian, penansIndigenous people are extremely important to the cultural and ethnic mix of Malaysian life. There are over 64 different groups of indigenous people in the country. Malaysia represents a tolerant society which respects the right of its people to practise any of the religions found there, i.e. Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and Christianity. In this respect, Malaysia has been successful in bringing together people from diverse cultures, countries and background to create a unified society.

Indigenous people form an integral part of Malaysian society and contribute greatly to the cultural richness of the country. The ethnic groups are quite diverse, speaking their own languages and practicing their own religions. However, these ethnic groups can remain locked in their own respective ethnic universe, isolated from the rest of society unless these differences are mitigated through infrastructure and development.

Today, indigenous people hold sway in the government and senior public positions. Government reforms have helped overcome ethnic divisions and aim to provide indigenous people with the same opportunities as other members of Malaysian society.

Government policy has focused on concerted developments in rural areas. Housing, schools and healthcare facilities are built close to the villages of indigenous people so they are not forced to move to urban areas. As a result of these developments, mortality rates have dropped and poverty is being alleviated. Perhaps most important of all is the fact that through education, indigenous people are taking greater control of their lives. Many have grasped the opportunities afforded by education and, at the same time, respect and follow the culture of their villages, proving that modern life can be compatible with traditional ways.

In Sarawak there are 26 different ethnic groups making up 70% of the state's 1.7 million inhabitants. The total land area of Sarawak is 12.3m hectares which is roughly 2.3 times the size of Holland. Virtually all of the ethnic people of Sarawak live off the land. They farm, fish, hunt and many of them practice shifting cultivation.

Indigenous people in Sabah accounts for 86.3% of the total Sabah population of 1.6 million. The vast majority of indigenous communities live in rural area and include ethnic groups such as the Kadazan, Bajau, Suluk and Cocos Malay. As in Sarawak, almost all of these people live off the land.

Penans

Professionals, including anthropologists and sociologists, in consultation with the Penans have drawn up these programmes to ensure that they are not left behind as the country move ahead towards achieving a newly industrialised country status in the year 2020. Short term programmes drawn up are intended to provide the Penans with basic need such as medicine, clothing's, building materials and agriculture tools while long-term programmes are drawn up to bring the community to the mainstream of society.

Recently, the Sarawak Government reported that the state Government's effort in getting the Penan community to lead a settled life and interact with other races in the country have met with much success. The Penans are now much aware of the goings-on surrounding them, parents are more willing to send their children to schools, clinics are well patronised and the infant mortality rate has dropped significantly.

Many Penans have adapted well to modern living and quite a number of them now work in government sector, as government servants, tourist guides and truck drivers. The government is currently working out new strategies to further develop the Penans into a thriving community.

Of the entire Penan population, about 400 of them are nomadic. 65,700 hectares of primary forests have been specially set aside for them so that they can continue to follow their nomadic lifestyles. This includes the Mulu National park (52,900 ha), Sungai Magoh (5,600 ha), Ulu Sungai Tutoh (2,200 ha) and Sungai Adang (5,000 ha).

For Penans who have settled in longhouses, but wish to pursue their traditions, the government has set aside Melana Protected Forest (22,000 ha) and an area in Ulu Seridan (1,400 ha). The places listed are not the only places where the Penans can practice their traditional way of life for they could also do so in the existing forest areas where they live as provided by Section 65 of the State Forest ordinance.

Culture of Malaysia

Posted by jeng_llot at Thursday, May 14, 2009 Labels: chinese, culture, indian, malaysianALTERNATIVE NAMES

Outsiders often mistakenly refer to things Malaysian as simply "Malay," reflecting only one of the ethnic groups in the society. Malaysians refer to their national culture as kebudayaan Malaysia in the national language.

ORIENTATION

Identification. Within Malaysian society there is a Malay culture, a Chinese culture, an Indian culture, a Eurasian culture, along with the cultures of the indigenous groups of the peninsula and north Borneo. A unified Malaysian culture is something only emerging in the country. The important social distinction in the emergent national culture is between Malay and non-Malay, represented by two groups: the Malay elite that dominates the country's politics, and the largely Chinese middle class whose prosperous lifestyle leads Malaysia's shift to a consumer society. The two groups mostly live in the urban areas of the Malay Peninsula's west coast, and their sometimes competing, sometimes parallel influences shape the shared life of Malaysia's citizens. Sarawak and Sabah, the two Malaysian states located in north Borneo, tend to be less a influential part of the national culture, and their vibrant local cultures are shrouded by the bigger, wealthier peninsular society.

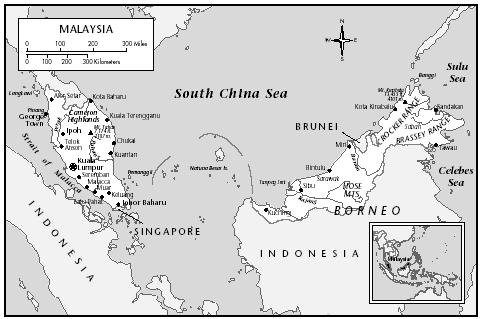

Location and Geography. Malaysia is physically split between west and east, parts united into one country in 1963. Western Malaysia is on the southern tip of the Malay peninsula, and stretches from the Thai border to the island of Singapore. Eastern Malaysia includes the territories of Sabah and Sarawak on the north end of Borneo, separated by the country of Brunei. Peninsular Malaysia is divided into west and east by a central mountain range called the Banjaran Titiwangsa. Most large cities, heavy industry, and immigrant groups are concentrated on the west coast; the east coast is less populated, more agrarian, and demographically more Malay. The federal capital is in the old tinmining center of Kuala Lumpur, located in the middle of the western immigrant belt, but its move to the new Kuala Lumpur suburb of Putra Jaya will soon be complete.

Demography. Malaysia's population comprises twenty-three million people, and throughout its history the territory has been sparsely populated relative to its land area. The government aims for increasing the national population to seventy million by the year 2100. Eighty percent of the population lives on the peninsula. The most important Malaysian demographic statistics are of ethnicity: 60 percent are classified as Malay, 25 percent as of Chinese descent, 10 percent of Indian descent, and 5 percent as others. These population figures have an important place in peninsular history, because Malaysia as a country was created with demography in mind. Malay leaders in the 1930s and 1940s organized their community around the issue of curbing immigration. After independence, Malaysia was created when the Borneo territories with their substantial indigenous populations were added to Malaya as a means of exceeding the great number of Chinese and Indians in the country.

Linguistic Affiliation. Malay became Malaysia's sole national language in 1967 and has been institutionalized with a modest degree of success. The Austronesian language has an illustrious history as a lingua franca throughout the region, though English is also widely spoken because it was the administrative language of the British colonizers. Along with Malay and English other languages are popular: many Chinese Malaysians speak some combination of Cantonese, Hokkien, and/or Mandarin; most Indian Malaysians speak Tamil; and

numerous languages flourish among aboriginal groups in the peninsula, especially in Sarawak and Sabah. The Malaysian government acknowledges this multilingualism through such things as television news broadcasts in Malay, English, Mandarin, and Tamil. Given their country's linguistic heterogeneity, Malaysians are adept at learning languages, and knowing multiple languages is commonplace. Rapid industrialization has sustained the importance of English and solidified it as the language of business.

Symbolism. The selection of official cultural symbols is a source of tension. In such a diverse society, any national emblem risks privileging one group over another. For example, the king is the symbol of the state, as well as a sign of Malay political hegemony. Since ethnic diversity rules out the use of kin or blood metaphors to stand for Malaysia, the society often emphasizes natural symbols, including the sea turtle, the hibiscus flower, and the orangutan. The country's economic products and infrastructure also provide national logos for Malaysia; the national car (Proton), Malaysia Airlines, and the Petronas Towers (the world's tallest buildings) have all come to symbolize modern Malaysia. The government slogan "Malaysia Boleh!" (Malaysia Can!) is meant to encourage even greater accomplishments. A more humble, informal symbol for society is a salad called rojak, a favorite Malaysian snack, whose eclectic mix of ingredients evokes the population's diversity.

HISTORY AND ETHNIC RELATIONS

Emergence of the Nation. The name Malaysia comes from an old term for the entire Malay archipelago. A geographically truncated Malaysia emerged out of the territories colonized by Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Britain's representatives gained varying degrees of control through agreements with the Malay rulers of the peninsular states, often made by deceit or force. Britain was attracted to the Malay peninsula by its vast reserves of tin, and later found that the rich soil was also highly productive for growing rubber trees. Immigrants from south China and south India came to British Malaya as labor, while the Malay population worked in small holdings and rice cultivation. What was to become East Malaysia had different colonial administrations: Sarawak was governed by a British family, the Brookes (styled as the "White Rajas"), and Sabah was run by the British North Borneo Company. Together the cosmopolitan hub of British interests was Singapore, the central port and center of publishing, commerce, education, and administration. The climactic event in forming Malaysia was the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia from 1942-1945. Japanese rule helped to invigorate a growing anti-colonial movement, which flourished following the British return after the war. When the British attempted to organize their administration of Malaya into one unit to be called the Malayan Union, strong Malay protests to what seemed to usurp their historical claim to the territory forced the British to modify the plan. The other crucial event was the largely Chinese communist rebellion in 1948 that remained strong to the mid-1950s. To address Malay criticisms and to promote counter-insurgency, the British undertook a vast range of nation-building efforts. Local conservatives and radicals alike developed their own attempts to foster unity among the disparate Malayan population. These grew into the Federation of Malaya, which gained independence in 1957. In 1963, with the addition of Singapore and the north Borneo territories, this federation became Malaysia. Difficulties of integrating the predominately Chinese population of Singapore into Malaysia remained, and under Malaysian directive Singapore became an independent republic in 1965.

National Identity. Throughout Malaysia's brief history, the shape of its national identity has been a crucial question: should the national culture be essentially Malay, a hybrid, or separate ethnic entities? The question reflects the tension between the indigenous claims of the Malay population and the cultural and citizenship rights of the immigrant groups. A tentative solution came when the Malay, Chinese, and Indian elites who negotiated independence struck what has been called "the bargain." Their informal deal exchanged Malay political dominance for immigrant citizenship and unfettered economic pursuit. Some provisions of independence were more formal, and the constitution granted several Malay "special rights" concerning land, language, the place of the Malay Rulers, and Islam, based on their indigenous status. Including the Borneo territories and Singapore in Malaysia revealed the fragility of "the bargain." Many Malays remained poor; some Chinese politicians wanted greater political power. These fractures in Malaysian society prompted Singapore's expulsion and produced the watershed of contemporary Malaysian life, the May 1969 urban unrest in Kuala Lumpur. Violence left hundreds dead; parliament was suspended for two years. As a result of this experience the government placed tight curbs on political debate of national cultural issues and began a comprehensive program of affirmative action for the Malay population. This history hangs over all subsequent attempts to encourage official integration of Malaysian society. In the 1990s a government plan to blend the population into a single group called "Bangsa Malaysia" has generated excitement and criticism from different constituencies of the population. Continuing debates demonstrate that Malaysian national identity remains unsettled.

Ethnic Relations. Malaysia's ethnic diversity is both a blessing and a source of stress. The melange makes Malaysia one of the most cosmopolitan places on earth, as it helps sustain international relationships with the many societies represented in Malaysia: the Indonesian archipelago, the Islamic world, India, China, and Europe. Malaysians easily exchange ideas and techniques with the rest of the world, and have an influence in global affairs. The same diversity presents seemingly intractable problems of social cohesion, and the threat of ethnic violence adds considerable tension to Malaysian politics.

URBANISM, ARCHITECTURE, AND THE USE OF SPACE

Urban and rural divisions are reinforced by ethnic diversity with agricultural areas populated primarily by indigenous Malays and immigrants mostly in cities. Chinese dominance of commerce means that most towns, especially on the west coast of the peninsula, have a central road lined by Chinese shops. Other ethnic features influence geography: a substantial part of the Indian population was brought in to work on the rubber plantations, and many are still on the rural estates; some Chinese, as a part of counter-insurgency, were rounded up into what were called "new villages." A key part of the 1970s affirmative action policy has been to increase the number of Malays living in the urban areas, especially Kuala Lumpur. Governmental use of Malay and Islamic architectural aesthetics in new buildings also adds to the Malay urban presence. Given the tensions of ethnicity, the social use of space carries strong political dimensions. Public gatherings of five or more people require a police permit, and a ban on political rallies successfully limits the appearance of crowds in Malaysia. It is therefore understandable that Malaysians mark a

FOOD AND ECONOMY

Food in Daily Life. Malaysia's diversity has blessed the country with one of the most exquisite cuisines in the world, and elements of Malay, Chinese, and Indian cooking are both distinct and blended together. Rice and noodles are common to all cuisine; spicy dishes are also favorites. Tropical fruits grow in abundance, and a local favorite is the durian, known by its spiked shell and fermented flesh whose pungent aroma and taste often separates locals from foreigners. Malaysia's affluence means that increasing amounts of meat and processed foods supplement the country's diet, and concerns about the health risks of their high-fat content are prominent in the press. This increased affluence also allows Malaysians to eat outside the home more often; small hawker stalls offer prepared food twenty-four hours a day in urban areas. Malaysia's ethnic diversity is apparent in food prohibitions: Muslims are forbidden to eat pork which is a favorite of the Chinese population; Hindus do not eat beef; some Buddhists are vegetarian. Alcohol consumption also separates non-Muslims from Muslims.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. When Malaysians have guests they tend to be very fastidious about hospitality, and an offer of food is a critical etiquette requirement. Tea or coffee is usually prepared along with small snacks for visitors. These refreshments sit in front of the guest until the host signals for them to be eaten. As a sign of accepting the host's hospitality the guest must at least sip the beverage and taste the food offered. These dynamics occur on a grander scale during a holiday open house. At celebrations marking important ethnic and religious holidays, many Malaysian families host friends and neighbors to visit and eat holiday delicacies. The visits of people from other ethnic groups and religions on these occasions are taken as evidence of Malaysian national amity.

Basic Economy. Malaysia has long been integrated into the global economy. Through the early decades of the twentieth century, the Malay peninsula was a world leader in the production of tin (sparked by the Western demand for canned food) and natural rubber (needed to make automobile tires). The expansion of Malaysia's industrialization heightened its dependence on imports for food and other necessities.

Land Tenure and Property. Land ownership is a controversial issue in Malaysia. Following the rubber boom the British colonial government, eager to placate the Malay population, designated portions of land as Malay reservations. Since this land could only be sold to other Malays, planters and speculators were limited in what they could purchase. Malay reserve land made ethnicity a state concern because land disputes could only be settled with a legal definition of who was considered Malay. These land tenure arrangements are still in effect and are crucial to Malay identity. In fact the Malay claim to political dominance is that they are bumiputera (sons of the soil). Similar struggles exist in east Malaysia, where the land rights of indigenous groups are bitterly disputed with loggers eager to harvest the timber for export. Due to their different colonial heritage, indigenous groups in Sarawak and Sabah have been less successful in maintaining their territorial claims.

Commercial Activities. Basic necessities in Malaysia have fixed prices and, like many developing countries, banking, retail, and other services are tightly regulated. The country's commerce correlates with ethnicity, and government involvement has helped Malays to compete in commercial activities long dominated by ethnic Chinese. Liberalization of business and finance proceeds with these ethnic dynamics in mind.