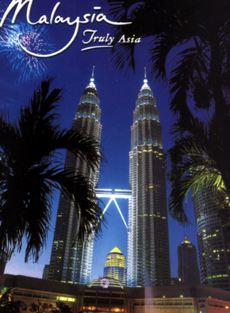

KUALA LUMPUR: Twin Towers rising like sentinels in the heart of Kuala Lumpur - that was the first picture of Malaysia to come into our minds when we were invited to this country.

A group of Malaysian women dressed in ethnic costumes welcome visitors in front of a building built in traditonal Malaysian style. [file photo] |

But what really excited us was that our hotel - the Mandarin Oriental - was right next door to the buildings. From the windows of our rooms, the glass-and-steel structures shone under a clear blue sky.

We couldn't resist rushing into the 88-storey towers, which soar 452 metres above street level, even before we had unpacked our luggage.

Costing a whopping US$1.2 billion, they were completed in 1997 and were the tallest in the world until 2003, when a higher building was completed in Taiwan.

"The towers helped Malaysian people build up their confidence," said Tan Sri Dr Noordin Sopiee, chairman and CEO of the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia. "What foreigners can do, we can do."

Towers of confidence

It was at the foot of the towers, that we, in our first ever visit to Malaysia, started our journey of understanding into this country.

The Petronas Twin Tower dominate the skyline of Kuala Lumpur. [China Daily] |

According to Sopiee, lack of confidence was a serious problem for Malaysia in the initial stages of its independence.

At the time, the multi-ethnic state was politically unstable, saddled with chronic and wide income, economic and development gaps, with few unifying features. It had been devastated by a civil war and race riots, had a feeble economic growth rate of only 3.5 per cent, an uneducated population, and no experience in democracy or self-rule.

"We once relied heavily on things like the Twin Towers - something the tallest, or the biggest, or fastest in the world - to help us develop self-confidence," Sopiee recalled. "We were once psychologically and culturally crippled."

Today, however, after 47 years of struggle, although Malaysia still faces some challenges, dramatic changes have taken place in the political, economic and social landscape.

Malaysia has evolved from a rubber and tin economy to become one of the world's most industrialized states, with a 7 per cent economic growth rate, 90 per cent of its exports manufactured goods, and no racial riots since 1968.

Moreover, the country is especially proud of its fast recovery from the Asian financial crisis - its GDP grew 7.4 per cent in the first quarter of this year and is expected to hit 6 to 6.5 per cent for the whole year. The banking sector, devastated by the crisis, has also been consolidated. In the disposal of bad bank loans, a recovery rate of as high as 57 per cent was achieved, compared with some 20 per cent in China.

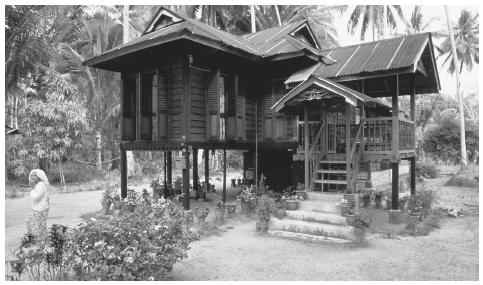

And its efforts to build a harmonious home for 27 ethnic groups, mainly Malay, Chinese and Indian, have paid off. Malay people account for 58 per cent of the country's total population, Chinese around 25 per cent and Indian 7 per cent, with other small groups making up the remaining 10 per cent.

In this nation of different religions - Islamism, Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, Christianity, Sikhism and Jainism - all the festivals of the different ethnic groups are respected. Several languages, mainly Malay, English and Chinese, are spoken.

"We feel pretty secure here now," said Siew Nyoke Chow, director and group editor-in-chief of the Chinese language Sin Chew Daily. "Malaysia has done a good job in this respect (unifying different ethnic groups)."

An often cited example of the harmonious relationship between different ethnic groups is the fact that many Malay people send their children to Chinese schools.

Nara Jantan, ISIS's senior public affairs and conference organizer, is one of them. She sent her daughter and son to Chinese primary schools.

"They are bilingual at home - we speak English and Malay. They can learn the third language - Chinese - in primary school. That's good for them," said the happy mother.

Actually, it is now very common for Malaysian people to speak several languages. We were surprised to find that most of the people we encountered during our 10-day stay spoke fluent English, even including ordinary taxi drivers and sales people in shopping centres.

To promote English education, the Malaysian Government even requires that mathematics and science courses to be taught in English in primary schools.

"Although Malay is the official language, most people speak English in offices," said Philip Mathews, ISIS Malaysia's co-director of the centre for international dialogue.

The centre's other co-director, Dr Stephen Leong, is even good at telling jokes both in Chinese and English.

But what surprised us even more is the fact that many Malaysian people can speak not only Mandarin Chinese, but also Cantonese and other Chinese local dialects.

Dato' Dr Ng Yen Yen, deputy finance minister, is one of them. When she tried to communicate with us in Cantonese, we could only reply, "Sorry, we can only speak Mandarin."

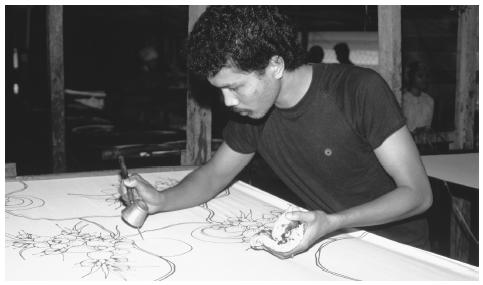

She said different cultures, different religions and different languages make Malaysia a typical Asian country, and that's what "Malaysia - Truly Asia" - the tourism advertisement often seen on CNN - means. Malaysia has spent millions of ringgit to promote this concept.

The deputy finance minister herself is an earnest advocator of the idea.

She wore a special dress when she met us, with the collar and buttons in Chinese qipao style, a Malaysian batik skirt, and a yellow Indian style shawl.

"With this dress, I can attend any gathering of Malay or Chinese people, and with the shawl, I can enter into any Indian temple," She said, adding that she had designed the golden dress herself.

The elegant government minister with her three-in-one dress and bright smile deeply impressed our group of 15 international journalists and researchers.

But she was not the only charming women we met during our stay in Malaysia.

Women's advancement

ISIS organized about a dozen interviews for us with senior officials, several of whom were women. In addition to Dato' Dr Ng Yen Yen, we also met Datuk Latifah Merican Cheong, assistant governor of the Central Bank of Malaysia, Dato' Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil, minister of women and family development. A female executive spoke to us about the operations of Petronas, Malaysia's national petroleum corporation, and a lady briefed us on the development of the nation's Multimedia Super Corridor.

Cheong, who supervises the central bank's foreign exchange control department, was the first high-ranking woman official we met.

Her eloquent oral presentation on Malaysia's economy and banking sector and to-the-point style when answering questions made us reassess our view and take note of the role of women in Malaysia's social and political arena.

We were later told that three ministries in this country are headed by women - the ministries of women and family development, international trade and industry, and youth and sports. And there are quite a few women deputy ministers as well.

Women architects and engineers are also active, many have participated in the design of Kuala Lumpur's famous skyscrapers. In universities, female students account for over 60 per cent of the total enrolment.

However, Dato' Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil, the minister of women and family development, believes that much still remains to be done to uplift women's status.

She admitted that there is still a need to educate men to fully accept gender equality, and said the concept must be taught in the home, and that women must show that they are "strong."

Her ministry has been holding seminars and training sessions to help women become economically independent.

But another problem now is that many well-educated, successful career women choose to stay home after they get married and have children, she said, adding that her ministry is working to promote job opportunities to allow women to work from their homes.

With her well-cared-for face and stylish dress, this woman minister had a hard time convincing us that she was 51.

"I will be a grandmother soon," said the mother of three children, smiling.

But when asked for her opinion on the possibility of Malaysia having a woman prime minister, she became serious.

"It won't be too long before that happens," she said.

Women organizations are also active in Malaysia. Sisters in Islam is one of them. It is a group of Muslim women studying and researching the status of women in Islam.

Unlike many Chinese women organizations which extend helping hands directly to women suffering from domestic violence and other unfair treatment, Sisters in Islam is mainly engaged in training and studying.

They have also gone to the courts to question discriminatory laws and they often write letters to the editors of newspapers to comment on cases of gender discrimination.

"It has been a long journey to where we are now," said Dato Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil. "But we have made great strides and no one can prevent us from reaching our goals."

That's true even for the whole of Malaysia, a country which has already bade farewell to poverty, racial riots, and political instability and moved onto a fast development track after decades of hard work.

Challenges

But it still faces new challenges - such as how to ensure the quality and speed of such development in the future.

Back in the 1990s, the Malaysian Government began to seriously consider how the approaching Information Age would affect Malaysia and how the country, currently manufacturing and export-oriented, must move to develop a knowledge-based economy.

Their answer was the initiation of the country's Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) in 1996.

"We aimed to cultivate a knowledge-rich society in Malaysia and take the country into the Information Age," said Sharifah Hendon Syed Hassan, with the Multimedia Development Corp, the developer of MSC.

The MSC is the nation's answer to the question of how to jumpstart the development of technology in the country. Physically, it is a 15-kilometre by 50-kilometre area reaching from Kuala Lumpur City Centre (KLCC) to the Kuala Lumpur International Airport.

The MSC is devoted to creating the best possible environment for multimedia companies wanting to create, distribute and employ multimedia products and services.

Several key areas such as e-government, multi-purpose cards and borderless marketing have been identified to spearhead the development of MSC, the official said.

Another ambitious plan is to build Putrajaya, the new administrative centre for the Federal Government of Malaysia which is about 40 minutes drive from KLCC.

Like all the big cities worldwide, Kuala Lumpur is a crowded city, with narrow streets full of private cars - mostly Protons made in Malaysia, shopping centres jam-packed with visitors from all over the world, and row upon row of skyscrapers.

To ease pressures in the overcrowded city and leave more downtown space for commercial activities, the Malaysian Government decided in the mid 1990s to build Putrajaya.

Named after Malaysia's first Prime Minister, Putrajaya has been dubbed Malaysia's first Intelligent Garden City. It is both the new nerve centre of the nation and an ideal place to live, work, conduct business and engage in sports and recreational activities.

This landmark complex stretches over 453 hectares. More than 70 per cent of Putrajaya is devoted to greenery and water with 13 different gardens.

Putrajaya Holdings, a company established to take charge of development of the new area, started construction of Putrajaya in 1996 and completed Phase 1 in 2000 with the delivery of infrastructure and key government buildings including the blue-domed Prime Minister's office and the red Putra Mosque - one of the largest in the nation. It is now in phase 2 of its development, which is expected to be completed in 2005.

Walking along the wide, flower-dotted roads in Putrajaya, appreciating all the brand-new buildings in different styles, or watching birds flying over the man-made lakes, we could not help admiring Malaysian people for building such a miracle in only five years.

If we agree that the Petronas Twin Towers were the source of confidence for Malaysian people in the 1990s, the MSC and Putrajaya will no doubt become the pride of the nation in the 21st century.